One digital history resource that has contributed a lot to my own interest in history would be GeaCron, an online virtual interactive map updated between 2011 and 2022 that depicts the distribution of historical states, kingdoms and empires for every year from 3000 BCE to the present as well as key events such as battles and voyages. While I discovered many historical topics for the very first time from GeaCron, its presentation of history is far from perfect in many areas, and in this post, I want to take a simple retrospective to analyze just how reliable of a historical resource it actually is. While the creators of GeaCron may not be planning to support the site for much longer in the future, you can view the current free version here: http://geacron.com/home-en/

Geacron.com was created by Luis Múzquiz, a Madrid-based computer specialist with degrees in geography and history. The website cites an extensive number of academic historical sources for the many time periods that it tries to cover, all of them secondary sources- mostly books, as well as some online databases. The books include both English and Spanish language sources, and are mostly by professional historians, but they include a handful of non-academic works of popular history such as Isaac Asimov’s “Chronology of the World”. The site does not go into any further detail about how or where different sources were used, nor do the books listed appear to be organized in any particular order. The online databases that Geacron draws upon are even more mixed- while some are well-curated university projects among them it also cites Wikipedia. The nature of the project means that the vast majority of the sources are those that involve maps or large-scale political histories.

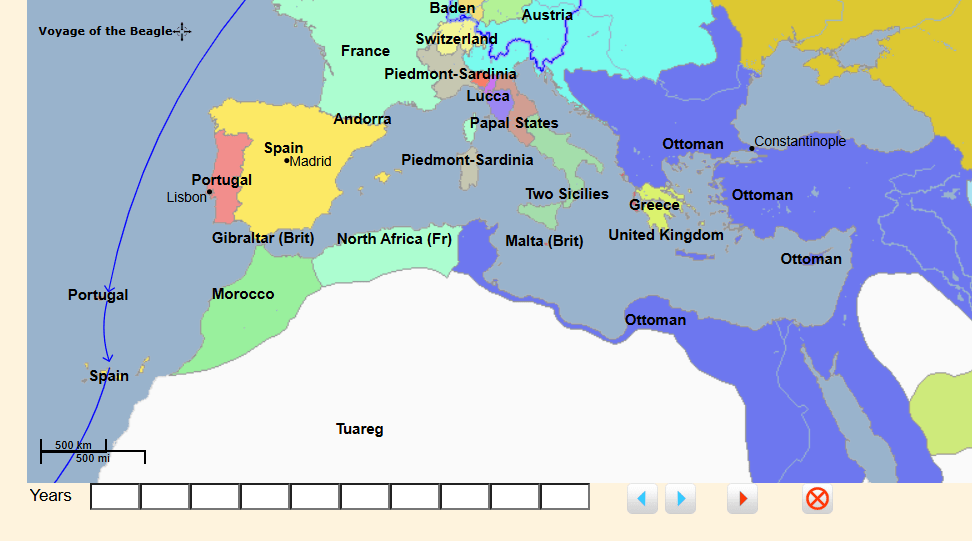

The page gives a brief explanation of the methodology of GeaCron that addresses some of the controversy in dating particular events for the ancient world, but it also gets to the heart of what I believe some of GeaCron’s greatest challenges are. It attempts to represent all of history from the Bronze Age to the present in the form of modern-style colorful maps of discrete sovereign states, effectively requiring an amalgamation of all kinds of conceptions of political territoriality that have existed throughout history into a very particular and somewhat binary framework that can’t straightforwardly be “mapped” from one era to the next.

GeaCron is fairly straightforward to navigate and use. The maps are easy to navigate back and forth, clearly labeled, and aesthetically sharp. Click on a location, and you will be able to open a link with more specific information. While most of the features are plainly intuitive, there isn’t a tutorial of any sort and I could see some of the elements being confusing to those who are unfamiliar.

In the bar at the bottom of the screen, one can bookmark particular years for quick and easy reference, but this isn’t outright explained. Overall, I would say that I like most of the design choices for what they are- the colors, labels and sidebars all make for vivid and engaging visuals that are absorbing to scroll through. While Geacron is available for free, most of the features beyond the basic map come with a twenty-nine Euro paywall, such as the links to further information, timelines and increased resolution of the map. In my opinion, the core of what makes GeaCron a worthwhile resource is all available for free, however. The cursory, digestible approach it takes to representing world history on a map is GeaCron’s main attraction, and any other information that it contains is largely accessible elsewhere. Moreover, applying scrutiny to GeaCron’s maps closely at the local level makes it more clear that the representation of discrete sovereign states often has severe limitations and inaccuracies for the majority of the time periods depicted, making the zoom resolution a feature with mixed value. GeaCron is best viewed as a jumping-off point for further engagement- it doesn’t impart comprehensive knowledge about any one place or time in particular, but for the less experienced in history, it stokes the imagination to see the array of places and times and think: things were happening here, events as complex and significant as the geopolitical tensions of today.

In conclusion, I would say that GeaCron has some, if limited, educational value. In terms of straightforward reliability, it is a facile tool to get a surface-level understanding of what the world was like at any given point in time. However, my impression from using GeaCron periodically over the years is that as a project it may have been somewhat over-ambitious in scope. In its description, GeaCron states that it seeks to be the “most powerful geo-temporal tool for history research, education, and findings dissemination”, that streamlines and synthesizes the overwhelming amount of history knowledge that can be found online, but the lack of detail and nuance that comes with the GeaCron project make it less than actually useful to anyone attempting to gain serious understanding. If GeaCron has a way of challenging narratives or bringing marginalized histories to light, it is in the fact that it puts all historical events in broader context- while observing the growth of one empire or civilization one can see how the rest of the world fared at the same time. Yet, it could also reinforce some significant misconceptions by back-projecting modern conceptions of statehood to historical periods where they are not necessarily applicable.

Overall, if you think that you know something or other about the contours of global history in just about every given place, GeaCron may not have much to offer. But if you find yourself drawing a complete blank for knowledge of any epoch of history, it may be worth checking out- you could discover something totally new.

Leave a comment