A dream in words. So what?

—

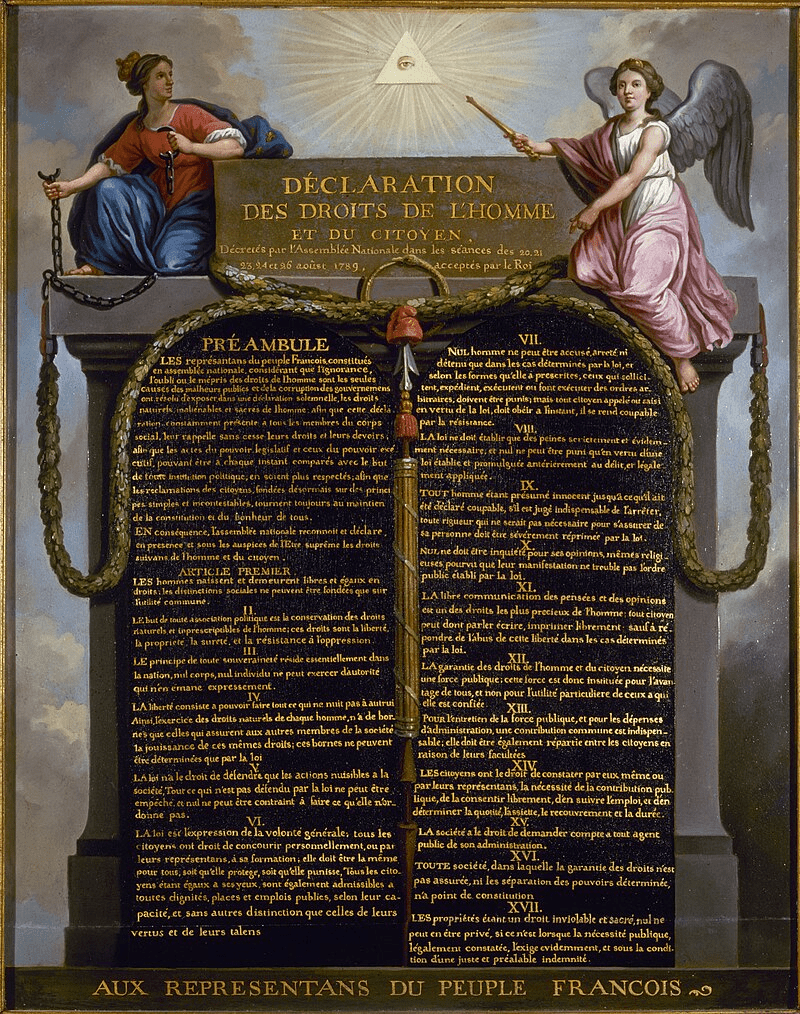

In August of 1789, it was by no means clear that the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen published by the newly constituted National Assembly of France would rock the foundations of societies worldwide as profoundly as it did. The Declaration’s affirmations that all men were endowed with a wide range of fundamental rights and freedoms were certainly radical and unheard of for their time, more emphatic, specific and detailed than any comparable language in the American Declaration of Independence only 13 years earlier. Yet, the Declaration carried no legal weight at this early stage in the French Revolution- it was a statement of abstract principles at best, self-congratulatory propaganda at worst. The National Assembly, comprised exclusively of white men of propertied classes, would take a pragmatic course that only extended the Declaration’s principles so far in the drafting of a true constitution for France, rejecting the ideas of an expanded suffrage, limiting or abolishing colonial slavery, or even disempowering the monarchy.

With the six word caption above I wanted to capture the feeling of inspiration and wonder mixed with deep ambiguity that the publication of the Declaration of the Rights of Man inspired in France and soon the world at large. Some questioned the value of such a Declaration as an ultimately empty statement but in reality, the dissemination of such a profound egalitarian document for the public became an incredible source of legitimacy for those who insisted that the reforms of the National Assembly did not go far enough and further revolutionary actions were necessary- in the public imagination, the Assembly was increasingly criticized for appearing to turn their backs on the very principles that they had first professed. And even while the National Assembly sought to contain the growing radicalism that it had inadvertently unleashed, the content of the Declaration itself would prompt the birth of wholly new and more radical discourses in response to it, such as whether it was just to declare the equality of all men to the exclusion of women, or whether collective rights to welfare and dignity were just as important as the rights to individual freedom and autonomy.

Image Credit: Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen, painting by Jean-Jacques-François Le Barbier circa 1789. Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a comment